Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels | |

|---|---|

Engels in 1879 | |

| Born | 28 November 1820 Barmen, Jülich-Cleves-Berg, Prussia |

| Died | 5 August 1895 (aged 74) London, England |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Mary Burns (died 1863) |

| Education | |

| Education | Gymnasium zu Elberfeld (withdrew) University of Berlin (withdrew) |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Main interests | |

| Notable works | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Signature | |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

Friedrich Engels (German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈɛŋl̩s]; 28 November 1820 – 5 August 1895) was a German philosopher, political theorist, journalist, businessman, and revolutionary socialist. He is best known for his lifelong collaboration with Karl Marx, with whom he co-authored The Communist Manifesto (1848) and developed the political and philosophical system that came to be known as Marxism. After Marx's death, Engels served as the editor of his works, completing the second and third volumes of Das Kapital.

Born in Barmen, Prussia, to a prosperous mercantile family, Engels rejected his family's devoutly pietistic values from a young age. He became involved with the Young Hegelians while performing military service in Berlin and embraced a materialist philosophy. In 1842, his father sent him to Manchester, England, to work in a cotton mill in which the family had an investment. His experiences of the industrial working class there led him to write his first major work, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845).

In 1844, Engels began a permanent partnership with Marx in Paris. Together they worked to critique the prevailing idealist philosophies and develop their materialist conception of history, notably in The Holy Family (1845) and The German Ideology (unpublished in their lifetimes). They became active in the Communist League, which commissioned them to write the Manifesto. Engels participated actively in the Revolutions of 1848, including in armed combat, before being forced into exile in England. From 1850, he lived in Manchester and worked for the family firm of Ermen & Engels for two decades, leading a double life as a respectable cotton merchant while providing crucial financial support to the impoverished Marx family in London.

After retiring in 1870, Engels moved to London and took on a central role in the International Workingmen's Association. Following Marx's death in 1883, he devoted the rest of his life to editing Marx's writings and acting as the leading authority on their shared philosophy. His own works, particularly Anti-Dühring (1878) and Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880), were instrumental in popularizing Marxism and became foundational texts for the Second International. Engels's application of dialectics to science in works like Dialectics of Nature was later controversially developed into the state ideology of the Soviet Union. He died of cancer in London in 1895, and his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head.

Early life (1820–1841)

[edit]Upbringing in Barmen

[edit]Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen, in the Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg of Prussia (later in Rhine Province; now part of Wuppertal in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany).[1] He was the eldest of nine children born to Friedrich Engels Sr., a prosperous cotton mill owner, and Elise Franziska Mauritia von Haar, the daughter of a schoolmaster.[2] The Engels family were devout Protestants and belonged to the Pietist movement, an influential form of German Lutheranism that stressed personal devotion and practical faith.[3] This background instilled in Engels a deep religiosity in his youth, marked by his 1837 Confirmation poem, but also exposed him to a Calvinist work ethic that fused worldly success with signs of divine grace.[4]

Engels grew up in the Wupper valley, an early industrial centre known as the "German Manchester".[6] His childhood home was part of a family compound surrounded by factories, workers' tenements, and the family's commercial enterprises.[7] His great-grandfather had founded a firm for bleaching yarn, which had expanded to include a spinning mill and a lace-knitting factory.[8] From his earliest days, he was exposed to the harsh realities of industrialisation: polluted rivers, dangerous working conditions, and the stark contrast between the "spacious and sumptuous houses" of the merchant elite and the poverty of the working class.[9] The family business, Ermen & Engels, which his father co-founded with Dutch partners Godfrey and Peter Ermen in 1837, would later expand to include a major thread factory in Manchester.[10]

Despite the family's strict Pietist and commercial ethos, which valued industriousness and viewed pleasure as a "heathen blasphemy", Engels's home life was not without warmth.[11] His father was a keen musician who played the cello, and the family enjoyed chamber concerts of piano, cello, and bassoon.[12] His mother, Elise, was more humorous and well-read than her husband; he inherited her "cheerful disposition" and love of reading, and she fostered his intellectual curiosity, introducing him to German literature and giving him the complete works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as a Christmas present.[13] His maternal grandfather, Bernhard van Haar, a pastor and school headmaster, introduced him to classical mythology,[14] while his mother also told him stories of Greek heroes.[15] Concerned about his son's rebellious spirit, his father once discovered a "dirty book from a lending library, a romance of the thirteenth century" that the young Engels had been reading in secret.[16]

Education and early radicalism

[edit]From an early age, Engels chafed against the strictures of Barmen life. At fourteen, he was sent to the municipal Gymnasium (secondary school) in nearby Elberfeld, which was purportedly one of the finest in Prussia.[17] There, under the tutelage of his history and literature teacher, Dr. Johann Clausen, he developed a growing interest in the myths and romance of ancient Germania and the liberal nationalism of the Young Germany movement.[18] This romantic patriotism was an early intellectual influence, shaping his imagination with heroic legends like Siegfried, the dragon-slaying hero of the Nibelungenlied.[19] His early writings reveal a political romanticism that fused Byronic heroism with the recent struggle for Greek independence, as seen in his unfinished 1837 story, "A Pirate Tale", which showed a fascination with the "hardware of war".[20]

His father, concerned about his son's literary and philosophical leanings, withdrew him from the Gymnasium in September 1837, just nine months before his graduation and just before his seventeenth birthday.[21] The decision reflected both his father's authoritarianism and Engels's own desire to pursue literature as his "inner and real" career alongside his "outward profession" in business.[22] He was expected to join the family business, dashing his hopes of studying law at university. He spent a year being inducted into the family firm in Barmen, during which he read rationalist works such as David Strauss's The Life of Jesus (1835).[23] His youthful poetry turned into imitations of the poet Ferdinand Freiligrath, who was then employed as a clerk in a local business.[24] In July 1838 he was sent to Bremen for a commercial apprenticeship at the trading house of Heinrich Leupold, a linen exporter.[25]

Apprenticeship in Bremen

[edit]

The coastal air of Bremen, a free Hanseatic trading city, proved more congenial to Engels than the "low Barmen mists".[27] While working as a clerk handling international correspondence, he took full advantage of the city's more liberal social life.[28] He took dancing lessons, went horse-riding, swam in the Weser, and joined the Academy of Singing.[29] A suavely attractive and vain young man, he sported a moustache as a political statement and engaged in the student practice of fencing, boasting of duels fought to defend his honour.[30]

It was in Bremen that Engels began to write publicly. Using the pseudonym "Friedrich Oswald" to hide his identity from his family, he contributed cultural criticism and feuilletons to Karl Gutzkow's paper, Telegraph für Deutschland.[31] His most significant work of this period was Letters from Wuppertal (1839), a searing eyewitness account of the social conditions in his home region. A "sensational attack on hypocrisy in the valley towns",[32] it offered a brutal critique of the human costs of industrialisation—the exploitation of child labour, the rampant alcoholism, the "smoky factory buildings" and the red-dyed Wupper river—and linked this misery directly to the religious hypocrisy of the Pietist factory owners.[33] The publication of the Letters caused a severe conflict with his parents and established the basis for his later separation from them.[34]

During this time, Engels underwent a profound intellectual and spiritual transformation. Dissatisfied with the "narrow spiritualism" of Wuppertal Pietism, he began to question the central tenets of Christianity.[35] His reading of Strauss's The Life of Jesus, which treated the Gospels as historically contingent myths rather than literal truth, had shattered his faith.[36] After a period of intense doubt, he embraced his new status: "I am now a Straussian", he declared to friends in October 1839.[37] The psychological vacuum left by his lost faith was quickly filled by the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel's philosophical system, with its emphasis on the rational, ordered development of history as an unfolding of Spirit (Geist), instantly attracted him.[38] Engels adopted a form of modern Pantheism, merging divinity and reason with the developmental unfolding of the world. "The Hegelian idea of God has already become mine", he wrote, "and thus I am joining the ranks of the 'modern pantheists'".[39]

Philosophy and communism (1841–1844)

[edit]Berlin and the Young Hegelians

[edit]In September 1841, Engels began his one-year compulsory military service with the Royal Prussian Guards Artillery in Berlin.[40] He entered without conspicuous enthusiasm, hoping to "free myself from the military",[41] and his letters from this period show little serious interest in military studies, concentrating instead on the "ludicrous side of army life".[42] As a volunteer with a private income, he lived in lodgings and spent most of his time not on the parade ground but at the University of Berlin as a non-matriculated student.[43] He attended lectures on philosophy, most notably those of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who had been brought to Berlin by the Prussian authorities to combat the influence of the radical Young Hegelians.[44] Engels, however, sided firmly with the Hegelians, joining their "philosophical hue and cry" against Schelling.[45] He published two anonymous pamphlets critiquing Schelling's lectures: the first, Schelling and Revelation (1842), was a serious critique that served as a readable "plain man's guide to the Young Hegelian movement",[46] while the second, Schelling, Philosopher in Christ, was a satirical parody cleverly placed with a Pietist publisher.[47]

Engels became a prominent member of the Young Hegelian circle known as Die Freien ('The Free'), a group of aggressive, bohemian intellectuals who met in the city's beer cellars to debate philosophy and politics.[48] Its members included Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner.[49] This group pushed Hegel's philosophy in a radical, atheistic, and revolutionary direction.[50] They rejected Hegel's conservative interpretation, which saw the Prussian state as the culmination of reason, and instead used his dialectical method as a tool for critiquing religion and the state.[51] The work of Ludwig Feuerbach, particularly The Essence of Christianity (1841), was a major influence.[52] Feuerbach had argued that man had created God in his own image, alienating his own human essence onto an external being.[53] "We were all Feuerbachians for a moment", Engels later recalled of the book's liberating effect.[54] During this period, Engels co-authored with Edgar Bauer a mock-epic poem, The Insolently Threatened Yet Miraculously Rescued Bible, which depicted Karl Marx as a "swarthy chap from Trier, a marked monstrosity", raving with wild impetuosity.[55]

First period in Manchester

[edit]After completing his military service in October 1842, Engels returned briefly to Barmen.[56] On his way, he visited the offices of the Rheinische Zeitung in Cologne and had his first, "distinctly chilly," meeting with its editor, Marx.[57] Marx, wary of the radicalism of the Berlin Freien, viewed Engels as an ally of the Bauer brothers, with whom he was in conflict over their abstract and propagandistic style of politics.[58] In a letter at the time, Marx rejected what he called the "heaps of scribblings, pregnant with revolutionising the world and empty of ideas" from the Berlin group, which was "seasoned with a little atheism and communism (which these gentlemen have never studied)".[59] In Cologne, Engels also met Moses Hess, who claimed he converted Engels to communism, describing him as "an anno 1 revolutionary... the most avid of communists" after their discussions.[60]

Later that year, Engels's father sent him to Manchester to work as a clerk in the office of Ermen & Engels's Victoria Mill in Weaste, Salford.[61] This move, intended to steer him away from radical politics, had the opposite effect.[62] Manchester, the "shock-city" of the Industrial Revolution, provided Engels with the empirical evidence for the communist theories he had absorbed in Germany.[63] He arrived in the aftermath of the 1842 Plug Plot riots, a massive wave of strikes and working-class dissent that had been brutally suppressed.[64] In Manchester, he wrote, "it was forcibly brought to my notice that economic factors... play a decisive role in the development of the modern world".[65]

Engels began a relationship with Mary Burns, a young, spirited Irish factory worker.[66] She became his guide to the city's underworld, escorting him through the slums of Salford and the Irish ghetto of "Little Ireland", districts which would have been unsafe for a bourgeois German to enter alone.[67] Their relationship, which lasted twenty years until Mary's death in 1863, was a profound personal and political partnership that allowed Engels to document the "unmixed working peoples' quarters" of the city.[68] He also cultivated connections with the Chartist movement, befriending activists like George Julian Harney and James Leach, and frequented the Owenite Hall of Science, where he was impressed by the articulacy of the working-class socialists.[69] He developed a particular admiration for the Irish, writing, "Give me two hundred thousand Irish... and I will destroy the British monarchy".[70]

His research culminated in his first major work, The Condition of the Working Class in England (published in German in 1845). Considered his masterpiece,[72] the book was a devastating polemic, combining personal observation with official reports to create a harrowing portrait of industrial capitalism.[73] The book's subtitle, "From Personal Observation and Authentic Sources", suggested personal experience was paramount, but later scholarship has shown that his personal observations were of minor importance compared to his extensive use of written sources like newspapers, official reports, and pamphlets.[74] It presented a wholly unflattering account of the "possessing class" and its role in a competitive economic system, emphasizing the worst cases of poverty and degradation.[75] Engels detailed the squalor of the slums, the brutal exploitation in the factories, the "social murder" committed by the bourgeoisie, and the systematic spatial segregation of the city that hid this misery from view.[76]

The book was not just a piece of reportage; it was a work of communist theory that presented the proletariat not merely as a suffering class but as the historical agent of its own liberation, forged in the crucible of industrial cities.[77] It also represented the first application of historical materialism, structuring its account of English industrialisation around the growth of the productive forces and their impact on class structure, politics, and ideology.[78] As an empirical study that took a different "road" from Marx's more theoretical work, its methodological significance for Marx lay in introducing him to parliamentary inquiries and other empirical sources.[79] The book's analysis of the human-machine interface, which drew on his critique of conservative figures like Andrew Ure, highlighted the displacement effect of technology and the "war of all against all" it engendered under capitalist conditions.[80]

In his 1844 article for Marx's new journal Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher, "Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy", Engels first applied the Hegelian concept of alienation, previously used by Feuerbach in a religious context, to the economic realm, arguing that private property turned man into a commodity and alienated him from his true human essence.[81] Described by Marx as a "brilliant sketch" and by some scholars as the "founding document in the Marxian theoretical tradition",[82] the essay also provided a sophisticated analysis of classical economics, arguing that the instability of competition inevitably generated monopoly and economic crises.[83] The essay had an "overwhelming" effect on Marx, who was deeply impressed by it.[84] It provided a "short-cut" in his intellectual development by shifting his focus from philosophy to political economy, which for Marx was the "decisive intellectual test of a colleague".[85]

Collaboration with Marx (1844–1849)

[edit]Paris, Brussels, and the Manifesto

[edit]

In August 1844, on his way back to Germany, Engels stopped in Paris and met Marx for the second time at the Café de la Régence. This meeting sealed their lifelong friendship and collaboration. The friendly reception and immediate proposal to collaborate on a pamphlet stood in stark contrast to their chilly first meeting;[59] over ten days, they discovered their "complete agreement in all theoretical fields".[86] Their first joint project was a polemic against their former Young Hegelian associates, Bruno Bauer and his circle, published in 1845 as The Holy Family.[87] Marx, however, greatly expanded his own sections, turning the planned pamphlet into a book-length work, much to Engels's bemusement.[88] The final publication listed Engels as the lead author, reflecting his greater reputation at the time, though he later deferred to Marx, writing "I contributed practically nothing to it".[89] The work was a critique of the abstract idealism of the Bauer brothers, arguing instead that "history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims", a key step in Marx and Engels's break with Hegelian philosophy.[90]

After Marx was expelled from Paris, the pair moved to Brussels in 1845.[91] There, they worked on their next major manuscript, The German Ideology, which developed their materialist conception of history.[92] While they owed a debt to the German philosophical tradition, particularly Hegel's dialectic, Marx and Engels's innovation was to provide a materialist interpretation of it, arguing that their task was to "reconstitute the dialectic on the basis of empirical and historical study".[93] They rejected Hegel's idealism, which started from abstract concepts, and instead began with the material world and the activity of human beings within it.[94] The book argued that social structures, politics, and ideas (the "superstructure") are determined by the economic "base"—the mode of production and the resulting class relations. "It is not consciousness that determines life, but life that determines consciousness," they wrote.[95] The manuscript was never published in their lifetimes and was famously abandoned "to the gnawing criticism of the mice".[96] During this period, Engels and Marx also began organising a network of socialist groups, founding the Communist Correspondence Committee to link socialists across Europe.[97]

In 1847, this committee merged with the League of the Just, an émigré German artisan society. The reorganised group, renamed the Communist League, commissioned Marx and Engels to write a program for the organisation.[98] Engels drafted two versions, the Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith and Principles of Communism, both in a catechism format.[99] He later suggested they abandon the catechism form and call it The Communist Manifesto.[100] The final text, written primarily by Marx but drawing heavily on Engels's drafts and their shared outlook developed in The German Ideology, was published in February 1848.[101] It famously declared that "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles"[102] and ended with the call: "Working Men of All Countries, Unite!"[103] While some scholars have highlighted divergences between Engels's drafts and Marx's final text, the fundamental arguments were shared, and the documents reveal more similarity than difference.[104] This period marked the height of their joint work, and the question of the precise nature of their intellectual relationship and any potential divergences—what would later be termed the "Engels problem"—would become a central feature of 20th-century Marxist scholarship.[105]

Revolutions of 1848

[edit]

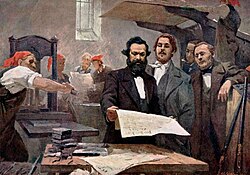

The publication of the Manifesto coincided with the outbreak of the Revolutions of 1848, beginning in France and quickly spreading across Europe. Marx and Engels moved from Brussels to Paris and then to Cologne, where they launched the Neue Rheinische Zeitung as a daily newspaper to support the democratic revolution in Germany.[106] Their strategy was to support a bourgeois revolution as a necessary precursor to a later proletarian one. The paper advocated a unitary, democratic German republic, criticised the Prussian monarchy and the vacillation of the liberal bourgeoisie at the Frankfurt Assembly, and called for war with Russia as the mainstay of reaction in Europe.[107] Engels's special province at the paper was military and diplomatic commentary, where he used his analyses to encourage revolutionary action.[108]

As the counter-revolution gained strength in late 1848, the authorities cracked down on the newspaper. After a mass rally in Cologne, martial law was declared, and an arrest warrant was issued for Engels on charges of high treason.[109] He fled to Brussels, but was arrested and deported to France, from where he walked across the country to Switzerland.[110] In May 1849, as the struggle for the Imperial Constitution reignited in Germany, Engels returned to his hometown of Elberfeld to join the uprising.[111] He served as Inspector of Barricades and helped recruit the military chief,[112] but was soon expelled by the bourgeois Committee of Public Safety, who feared his "red-radical" presence.[113] He then travelled south to join the Baden-Palatinate revolutionary army as an aide-de-camp to August Willich, partly to gain "a bit of military education" and, as he wrote to Marx's wife Jenny, to save the reputation of their newspaper.[114] He participated in four military engagements against the Prussian forces, including the major battle at the Rastatt Fortress.[115] After the defeat of the insurgents, he escaped to Switzerland in July 1849, among the last of the retreating revolutionary army to cross the border.[116] This experience of revolutionary incompetence shaped his later distrust of amateurism and spontaneity in warfare.[117]

Manchester years (1849–1870)

[edit]Return to commerce

[edit]

After the defeat of the 1848 revolutions, Engels and Marx reunited in London in late 1849.[119] They found themselves in an impoverished and fractious émigré community, still convinced that another revolutionary wave was imminent.[120] However, as the European economy recovered and Marx's family sank into desperate poverty, Engels made a momentous decision. In November 1850, reconciling with his family, he agreed to return to Manchester and resume his position at the Ermen & Engels office to provide financial support for Marx.[121] "Huckstering is too beastly," he later wrote to Marx, but he endured this "purgatory" for nearly twenty years.[122] This period of his life was a "nervous, sapping sacrifice" in which he led a double life as a respectable, middle-class businessman and a clandestine communist revolutionary.[123]

Engels proved to be an effective and industrious businessman. He unpicked the firm's finances for his father, successfully navigated office politics, and rose through the ranks, becoming a partner in the firm in 1864.[124] His income grew substantially, reaching over £1,000 a year by 1860, a sum which placed him comfortably in the upper-middle class.[125] Over twenty years, he sent a constant stream of funds to the Marx family in London, totalling between £3,000 and £4,000, effectively funding Marx's research and the writing of Das Kapital.[126]

This "double life" required elaborate arrangements. He maintained an official residence in respectable city suburbs while living secretly with Mary Burns, and later her sister Lizzy, in a series of modest houses in working-class districts like Chorlton and Ardwick.[127] In his public life, Engels became a stalwart of Manchester society. He was a member of the Royal Exchange, the Schiller Anstalt (the German community's institute), and exclusive gentlemen's clubs like the Albert Club and the Brazenose Club.[128] A passionate equestrian, he regularly rode with the Cheshire Hounds, one of the most aristocratic fox hunts in England, which he also considered practical training for cavalry service.[129]

Intellectual work and personal life

[edit]

Despite the demands of his business and the self-loathing he felt for his "accursed commerce", Engels continued his intellectual collaboration with Marx. Their near-daily correspondence reveals the depth of their partnership.[130] After 1846, Engels did little further independent work on economic analysis, focusing instead on his political and historical journalism.[131] He acted as Marx's ghostwriter for hundreds of articles for the New-York Daily Tribune, for which Marx was the European correspondent but whose English was initially poor.[132] Beginning in the late 1850s, both he and Marx undertook a "return to Hegel", renewing their interest in dialectics and engaging with contemporary developments in the natural sciences, such as the work of Charles Darwin.[133] He maintained a close friendship and intellectual exchange with the chemist Carl Schorlemmer, who was also based in Manchester and provided Engels with his "only direct contact with advanced institutionalised natural science".[134]

In 1850, reflecting on the defeat of the 1848 revolutions, Engels wrote The Peasant War in Germany, one of his first major historical works.[135] The book served as an analogy, arguing that the 1848–49 uprising had failed for the same reason the 16th-century German Peasants' War had: the German bourgeoisie was too timid and compromised to challenge the aristocracy and lead the revolution.[136] He drew parallels between the two events to provide lessons for the contemporary revolutionary movement and offer a "rich revolutionary antecedent" in a country with a seemingly weak revolutionary tradition.[136] Applying the method of historical materialism, Engels analyzed the religious conflicts of the Reformation as fundamentally expressions of underlying class conflict, arguing that the peasant and plebeian insurgents, led by radical figures like Thomas Müntzer, articulated their social and economic grievances in religious terms.[137]

Engels also became a respected military analyst, writing extensively on the Crimean War, the Franco-Austrian War, and the American Civil War, earning the nickname "The General" in Marx's household.[138] As a military analyst, Engels focused on the intersection of technological, political, and economic factors in warfare, and became an expert on the technological transformations in naval strategy during the 1850s and 1860s.[139] His turn to serious military studies in the 1850s was not a matter of personal taste, but a direct response to conflict with the "military-putschist" faction of émigrés led by August Willich. Engels sought to counter their theories of revolution as a purely military affair by mastering the subject himself, so that, as he wrote, "at least one 'civilian' will be able to compete in matters of theory".[140]

In January 1863, Mary Burns died suddenly of a heart condition at the age of forty. Engels was devastated. "The poor girl loved me with all her heart," he wrote to Marx.[141] Their friendship was severely strained when Marx responded with a self-absorbed and unfeeling letter focused on his own financial troubles. After a rare apology from Marx, the breach was healed.[142] Sometime after Mary's death, Engels began a relationship with her sister, Lizzy Burns, who became his partner for the rest of her life.[143]

Crucially, Engels served as Marx's primary consultant for Das Kapital. He provided detailed, real-world information on the workings of capitalist industry, from machinery costs and bookkeeping practices to the structure of the cotton market,[144] and engaged in deep theoretical discussions with Marx on core concepts like constant and variable capital and the theory of surplus value.[145] He also served as Marx's "man on the ground" for analysing economic events; during the crisis of 1857, for example, he provided Marx with insider information from Manchester on business practices like "kite-flying" (speculative bill-jobbing), which Marx then used in his Books of Crisis and later in Das Kapital.[146] The long years of sacrifice were vindicated with the publication of the first volume of Das Kapital in 1867. Engels then set to work as Marx's most gifted publicist, writing numerous anonymous reviews to generate a "journalistic firestorm" and ensure the book's success.[147]

On 30 June 1869, at the age of 49, Engels finally retired from the business, having negotiated a settlement that gave him a substantial capital sum of £12,500 and a comfortable annual income.[148] "Hurrah! Today doux commerce is at an end, and I am a free man", he declared to his mother.[149] He celebrated by taking a long walk in the fields and drinking champagne with Lizzy and Marx's daughter Eleanor.[150]

London and later years (1870–1895)

[edit]The "Grand Lama" of Regent's Park Road

[edit]

In September 1870, Engels and Lizzy Burns moved to London, settling at 122 Regent's Park Road in Primrose Hill, a ten-minute walk from Marx's home.[152] His retirement from commerce allowed him to return fully to political life. He was immediately elected to the General Council of the International Working Men's Association and took charge as corresponding secretary for several European countries.[153] He played a key role in the International's internal struggles, particularly the bitter conflict with the anarchist faction led by Mikhail Bakunin.[154] Engels deployed his organisational skills and "passion for low politics" to defend Marx's authority and centralist vision for the movement, leading to Bakunin's expulsion at the Hague Congress in 1872.[155]

Engels's home became the intellectual and social centre of international socialism, earning him the nickname "The Grand Lama of the Regent's Park Road".[156] His week was regimented: mornings for study, afternoons for a visit to Marx, and evenings for correspondence.[157] On Sundays, he held an open house for the cream of European socialism, with visitors from Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein to William Morris and Keir Hardie attending gatherings fuelled by Pilsner beer, wine, and German folk songs.[158]

During the 1870s and 1880s, Engels produced some of his most important works. In response to the growing influence of the socialist theorist Eugen Dühring in Germany, and at the urging of German labour leaders who feared for party unity, Engels wrote a series of polemical articles that were collected as Anti-Dühring (1878).[159] The book, written with Marx's approval, was a comprehensive and accessible explanation of their shared "scientific socialism", covering philosophy, political economy, and history.[160] The impetus for the project appears to have come from Engels himself, who, in a "rage" over Dühring's influence, suggested to Marx that a thorough critique was necessary.[161] Although it led to the popularisation of three "dialectical laws" that later became a tenet of Marxism–Leninism, the term "dialectical law" itself originated with Marx in Das Kapital, and Engels first took it up in Anti-Dühring as part of his defence of Marx's work.[162] A section of it was later published separately as the highly influential pamphlet Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880), which contrasted Marxism with the "pure phantasies" of earlier socialists like Robert Owen and Charles Fourier.[163] By 1892, Engels noted that it had been translated more often than The Communist Manifesto or Das Kapital, circulating in ten languages in editions totalling around 20,000 copies.[164]

Drawing on his continuing research into the natural sciences, Engels also worked on Dialectics of Nature, a project that originated in a letter to Marx on 30 May 1873 in which he outlined his "dialectical ideas on the natural sciences".[165] It was an unfinished attempt to "rescue conscious dialectics from German idealist philosophy" and demonstrate that "the dialectical laws are real laws of development of nature".[166] He sought to outline a unified worldview on a scientific basis, encompassing nature and society under the same dialectical laws of motion, in line with the positivist spirit of the era.[167] He engaged with contemporary scientific developments, including detailed studies of electricity, which he believed heralded a "tremendously revolutionary" new era in industry.[168] His correspondence with Marx reveals that Marx's responses to this project were consistently brief and non-committal.[169] The work was left as a "torso"—a collection of notes and fragments rather than a finished book—after Engels was compelled to set it aside to write Anti-Dühring.[170] It was published posthumously in the Soviet Union in 1925, and though its science was by then obsolete, it fit into the scientistic orientation of Marxism which was reinforced during the Joseph Stalin era.[171]

Lizzy Burns suffered from a tumour of the bladder and died on 12 September 1878. Respecting what he presumed was her deathbed wish as a devout Catholic, Engels had married her the previous evening.[172]

After Marx's death: "First Fiddle"

[edit]

Karl Marx died on 14 March 1883. Engels, who arrived at the house minutes after his friend's passing, was shattered.[173] He delivered the graveside eulogy at Highgate Cemetery, comparing Marx's discoveries to those of Charles Darwin and declaring: "His name will endure through the ages, and so also will his work!"[174] Engels also summarized what he considered Marx's two great discoveries: "the law of development of human history" and "the special law of motion governing the present day capitalist mode of production".[175] After a lifetime as "second fiddle", Engels stepped into the role of the foremost authority and guardian of Marxism.[176] "Only now did he... show all he was capable of," recalled Wilhelm Liebknecht.[177]

Engels devoted the remainder of his life to two main tasks: editing and publishing Marx's literary estate and guiding the strategy of the growing international socialist movement.[178] His most significant undertaking was the Herculean task of deciphering Marx's near-illegible manuscripts to complete Das Kapital.[179] He published Volume II in 1885 and Volume III in 1894.[180] Engels did not simply transcribe the texts; lacking complete manuscripts, he had to view all of Marx's notes and summaries to provide structure and form to the books.[181] This was, in his own words, a "Sisyphean task", as Marx's drafts were a "real hotchpotch" of associative thoughts, digressions, and unfinished calculations.[182]

Engels's editorial interventions were not without controversy; in Volume III, he modified passages on economic crises in a way that downplayed the autonomous role of credit that Marx had increasingly emphasised, framing them instead as a result of overproduction, in line with Engels's own earlier views.[183] Confronted with Marx's own theoretical doubts regarding the law of the falling rate of profit, Engels presented a more coherent and confident text than the material warranted, inserting his own passages interpreting the law as predicting the inevitable collapse of capitalism.[184] His most controversial editorial decision was the argument, presented in a supplement to Volume III, that Marx's law of value operated in pre-capitalist societies for thousands of years—a claim that contradicted Marx's own historical analysis and which Engels later defended against critics like Werner Sombart.[185] While modern scholarship has noted these errors and editorial choices that tended to present Marx's drafts as more finished than they were, Engels's work is considered to have successfully preserved the core of Marx's critique.[186]

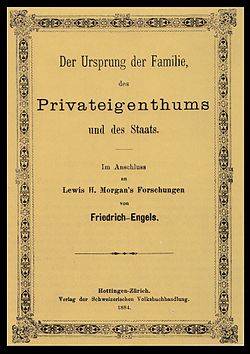

Using Marx's notes on the work of American anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan, Engels wrote The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884).[187] The book may have been written partly as a more historically grounded response to August Bebel's popular but utopian Women and Socialism (1879).[188] It traced the evolution of the family alongside the development of property relations, arguing that the patriarchal, monogamous family was a product of private property and marked the "world historic defeat of the female sex".[189] It became a foundational text of socialist feminism, arguing for a "unitary theory" that linked women's oppression to the structures of class society.[190] However, the work has been criticised for its flawed anthropological basis and its reliance on an idealist explanation for the rise of patriarchy: a presumed desire in men to pass on wealth to their own children.[191]

In his late correspondence, collected as the Letters on Historical Materialism, Engels worked to clarify the Marxist conception of history, distancing it from the vulgar economic determinism that was becoming prevalent in the socialist movement.[192] He insisted their view of history was "above all a guide to study", not an excuse for avoiding historical research, and that "All history must be studied afresh".[193] Engels argued that while the "production and reproduction of real life" was the "ultimately determining factor in history", the political and ideological superstructure was not a passive reflection of the economic base, but interacted with it and could "often determine the form of historical struggles".[194] He cautioned that he and Marx had been forced to "overemphasise the economic factor" in their polemics against idealist philosophy.[193] To explain historical causation, he used the metaphor of a "parallelogram of forces", where the historical event is the resultant of innumerable intersecting individual wills, each shaped by specific material conditions.[195]

Engels acted as the senior adviser to the parties of the Second International, founded in 1889.[196] He corresponded tirelessly with socialist leaders across Europe, offering tactical and ideological guidance, for example to the burgeoning socialist movement in Italy.[197] He was particularly critical of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) in Britain, which he accused of dogmatism and sectarianism. In an 1892 letter to Karl Kautsky, he described the SDF as having "ossified Marxism into a dogma" and failing to connect with the actual workers' movement.[198]

In his final years, Engels adapted his revolutionary strategy to the age of mass democracy. While not abandoning the moral right to insurgency, he argued that with universal suffrage, the working class could achieve power through the ballot box. This strategy of "revolutionary electoralism" was based on his conclusion that, following advances in military technology, a violent uprising against a modern army was "madness".[199] Revolution was only possible if the army itself became unreliable, an outcome he predicted as a result of universal conscription filling the ranks with socialist workers. In what has been called the "theory of the vanishing army", Engels argued that growing socialist electoral success was a measure of the army's internal state; once socialists comprised a critical mass of soldiers, the army would refuse to repress the population, effectively "vanishing" as a pillar of the capitalist state and opening a path to power.[200]

In his 1895 introduction to Marx's The Class Struggles in France, Engels wrote, "The time of surprise attacks, of revolutions carried through by small conscious minorities... is past," suggesting an electoral path to socialism, particularly for the rapidly growing Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).[201] The publication of this text was not without controversy. To placate the concerned SPD executive, Engels agreed to the omission of certain revolutionary passages. The SPD's main newspaper, Vorwärts, however, published an edited version that portrayed Engels as an advocate of a strictly peaceful, parliamentary path to power. Engels protested this distortion, writing to Paul Lafargue that such a policy of "peace at any price" was not his position.[202]

In March 1895, Engels was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus.[203] He died in London on 5 August 1895, at the age of 74.[204] In his will, he named Eduard Bernstein as one of his literary executors.[205] Following a secular funeral service at the Woking crematorium, his ashes were scattered at sea off Beachy Head.[206]

Personal life

[edit]Engels's personality was marked by jollity, a love of life, and what his associates called his Rhenish joyousness.[207] He was a keen conversationalist, a heavy drinker who celebrated political victories and defeats alike, and a lover of poetry, which he often recited.[208] His private letters reveal an artistic side, containing poems and cartoons of friends and acquaintances.[209] He was an accomplished linguist, able to correspond in numerous European languages, boasting to his sister that he could converse in 25.[210] Despite his bohemian tendencies, he maintained a strict Calvinist work ethic throughout his life.[207]

His most significant relationship was his forty-year friendship with Karl Marx, which one contemporary described as having a "tie passing the love of woman".[212] Engels was fiercely loyal to Marx, subordinating his own intellectual ambitions and financial security to support his friend. He became a second father to Marx's daughters—Jenny, Laura, and Eleanor—who affectionately called him "General" or "Uncle Angel".[213] Marx considered Engels his "alter ego".[214]

For over two decades, Engels's primary partners were the Irish working-class sisters Mary (c. 1822–1863) and Lizzy Burns (1827–1878). He lived with Mary from his first stay in Manchester until her sudden death, which devastated him.[215] He later began a relationship with Lizzy, praising her "genuine Irish proletarian blood" and "passionate feelings for her class".[216] He married Lizzy on her deathbed to satisfy her religious convictions.[217] These relationships stood in stark contrast to the bourgeois institution of marriage, which he condemned as a form of property relation amounting to "leaden boredom" and reducing the wife to a form of prostitute.[218] In a great act of friendship, Engels claimed paternity of Freddy Demuth, Marx's illegitimate son with the family's housekeeper, Helene Demuth, to save Marx's marriage. He revealed the truth to Eleanor Marx on his deathbed.[219] However, some scholars, such as Terrell Carver, have questioned this account, citing the unreliability of the primary source and suggesting that the evidence remains inconclusive.[220]

Legacy

[edit]Engels's legacy is inseparable from that of Marx, but his specific contributions and influence have been the subject of extensive debate. After Marx's death, Engels took on the role of the definitive interpreter of Marxist theory, codifying it into a comprehensive worldview.[221] His works, particularly Anti-Dühring and Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, became the primary texts through which generations of socialists, including leaders of the Second International like Karl Kautsky and Georgi Plekhanov, came to understand Marxism.[222] Following Engels's death, his 1895 introduction became a key text in the "revisionist controversy". Figures like Eduard Bernstein cited it to support their argument for an evolutionary, parliamentary path to socialism, emphasizing Engels's admission that he and Marx had been wrong in 1848 about the ripeness of economic conditions for revolution.[223] The failure of Engels's "theory of the vanishing army" to persuade his successors, who did not share his faith that socialist soldiers would defy their orders, created what has been called a "tactical vacuum" in revolutionary thought. Bereft of a convincing method for making the revolution happen, the socialist movement split between those who, like Bernstein, abandoned the revolutionary goal as impossible, and those who, like Georges Sorel and Vladimir Lenin, proposed new activist schemes such as the general strike or the vanguard party to fill the void.[224]

Many 20th-century critics, from the Western Marxist tradition of György Lukács to later scholars like Norman Levine, have argued that Engels distorted Marx's thought.[225] This "divergence thesis" holds that his "dialectics of nature" created a rigid, scientistic, and deterministic philosophy—"dialectical materialism"—that was alien to Marx's more humanistic and historical method.[226] Levine, for example, argues that Engels's philosophy was a "mechanistic materialism" and "social positivism" that stood in stark contrast to Marx's "dialectical naturalism".[227] The philosopher Leszek Kołakowski argued for a clear difference between Engels's "naturalistic evolutionism" and Marx's "dominant anthropocentrism", in which Marx's view was that nature is an extension of man, an "organ of practical activity".[228] He identified three other points of contrast between the two thinkers: a technical interpretation of knowledge versus the epistemology of praxis, the "twilight of philosophy" in science versus its merging into life as a whole, and infinite progression versus revolutionary eschatology.[229] In this view, Engels is held responsible for creating a "scientistic historical materialism" by misinterpreting Marx's concept of "material life" in terms of the materialism of the physical sciences,[230] an "Engelsian inversion" which laid the ideological groundwork for the dogmatism of Soviet Marxism and Stalinism.[231] Herbert Marcuse, for example, argued that Engels's Dialectics of Nature provided the "skeleton for the Soviet Marxist codification",[232] while Kołakowski claimed its effect was to "stifle sciences" in the Soviet Union.[233] According to this view, Engels was the "first believer in the mythic joint identity of Marx and Engels," and by appointing himself Marx's posthumous alter ego, he unintentionally created the conditions for this myth to flourish and be misappropriated by his successors.[234]

Other scholars argue that this view relies on a caricature of Engels's thought and that the evidence for a profound split is "flimsy".[235] They contend that Engels himself distinguished between the dialectic of nature and the dialectic of society. In Dialectics of Nature, for example, Engels argued that in nature, change occurs through a gradual merging of opposites, whereas in history, development occurs through sharp contradictions and an "either-or" struggle between opposing forces.[236] Similarly, in Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886), he wrote that dialectical laws were "identical in substance" between nature and society, but "different in their expression" in so far as human consciousness could be applied in one but not the other.[237] Even Lukács's critique, a key source for the divergence thesis, was not that Engels was wrong to believe in a dialectic of nature, but that he had failed to distinguish its form from the dialectic of society, which involves the conscious subject transforming its object.[238]

Biographer Tristram Hunt argues that the divergence thesis is a misreading of both Engels and the Marx-Engels collaboration. Marx was a "prime mover" behind Anti-Dühring and shared Engels's interest in the natural sciences.[239] The political theorist Paul Blackledge points out that Marx and Engels spoke of a shared project and that their extensive correspondence shows a profound intellectual dialogue.[240] Some scholars see the controversy as being "essentially a political rather than a philosophical debate", in which Engels is made a "scapegoat" for the later theoretical and political failures of Marxism.[241] Hunt contends that there is an "unconscionable philosophical chasm" between Engels's open and critical scientific socialism and the totalizing dogma of Stalinism, noting that Stalin gut Marxism of its revolutionary content and explicitly rejected key tenets of Engels's thought.[242] Engels consistently warned against turning their theory into a "rigid dogma of an orthodox sect" and stressed that "our view of history is first and foremost a guide to study, not a tool for constructing objects".[243] Hunt argues that the next generation of socialists, who came to Marxism through Darwin rather than Hegel, read his work through a different philosophical lens, for which he cannot be held responsible.[244]

Other scholars, such as Terrell Carver, argue that Engels's later theoretical works were a continuation of an independent intellectual project he began in his youth, long before his close collaboration with Marx. From this perspective, his popularisations were not a distortion of Marx but an expression of his own distinct, lifelong synthesis of Hegelian philosophy and scientific materialism.[245] According to Sven-Eric Liedman, Engels's work was shaped by the need to create a manifest ideology for the socialist movement, an ambition that led him to start his synthesis with the natural sciences rather than with social theory in a choice that inadvertently aligned his project with idealist philosophy rather than historical materialism.[246]

Engels's The Origin of the Family provided the first major discussion within the Marxist tradition on the relationship between class society and the subordination of women. Praised by early socialist feminists such as Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg, it became a key text in the socialist movement's approach to the "woman question", particularly its central argument that women's emancipation depended on their entry into social production.[247] However, the book has been subject to consistent criticism since its publication for its economic determinism and failure to adequately theorize the domestic sphere. Later feminists, including Simone de Beauvoir and Kate Millett, attacked its "over-deterministic materialism" and its failure to address the psychological dimensions of patriarchy.[248] Critics have also contrasted Engels's unilinear account of women's oppression—stemming from the "world historic defeat of the female sex" with the advent of private property—with Marx's more nuanced and multilinear analysis in his later Ethnological Notebooks, which found elements of oppression within earlier communal societies and granted more agency to women as historical subjects.[249] While some feminist anthropologists in the 1970s valued its materialist and historical approach as an alternative to universalist or biologistic explanations of female subordination,[250] Engels's analysis continues to occupy a central, if contested, role in feminist debates about the links between capitalism, patriarchy, and class conflict.[251]

In the 21st century, as post-1989 neoliberalism has faced challenges, Engels's voice has re-emerged as strikingly contemporary.[252] His critiques of global free markets, the instability of finance capitalism, urban segregation, and the "cosy collusion of government and capital" resonate with modern concerns.[252] His analysis of American capitalism, while ultimately failing to grasp the reasons for the weakness of its socialist movement, correctly identified the country's rising global economic power.[253] His ecological insights, particularly his warning in Dialectics of Nature that humanity does not "rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people", have been seen as prescient.[254] This ecological sensibility is also evident in his earlier urban writings. In The Condition of the Working Class and The Housing Question, Engels connected the environmental degradation of industrial cities—polluted air and water, unsanitary housing—directly to the class character of capitalism. This approach, linking public health, urban planning, and class struggle, has been influential in modern urban political ecology, which critiques proposed solutions to environmental problems (such as home ownership) that do not challenge the underlying structures of private property.[255] According to Hunt, as the "workshop of the world" shifts to countries like China, the social and environmental consequences of rapid industrialisation appear as an eerie echo of the conditions Engels described in 19th-century Manchester.[256]

Selected works

[edit]- The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)

- The Holy Family (1845) – with Marx

- The German Ideology (written 1846; first published 1932) – with Marx

- The Communist Manifesto (1848) – with Marx

- The Peasant War in Germany (1850)

- Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany (1852)

- Dialectics of Nature (written 1873–1886; first published 1925)

- Anti-Dühring (1878)

- Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880)

- The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884)

- Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886)

See also

[edit]- Engels, Saratov Oblast – City in Russia, renamed after Engels in 1931

- Friedrich Engels Guard Regiment – East German military unit

References

[edit]- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 11; Carver 1990, p. 1; Mayer 1969, p. 16; Henderson 1976, p. 2; Green 2008, p. 14; Marcus 1974, p. 67; Blackledge 2019, p. 21; Hunley 1991, p. 2.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 11, 18; Carver 1990, p. 4; Mayer 1969, p. 16; Green 2008, p. 15; Marcus 1974, p. 67.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 14; Carver 1990, p. 3; Carver 1983, p. 2; Mayer 1969, p. 16; Henderson 1976, p. 4; Green 2008, p. 16; Marcus 1974, p. 68; Blackledge 2019, p. 21; Hunley 1991, p. 2.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 15–16; Carver 1990, p. 8; Mayer 1969, p. 18; Rigby 1992, p. 28.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 14, plate 2; Hunley 1991, p. 2.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 14; Carver 1983, p. 2; Mayer 1969, p. 15; Henderson 1976, pp. 2–3; Green 2008, p. 16; Marcus 1974, p. 68.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 12; Carver 1990, p. 22; Henderson 1976, p. 3.

- ^ Schmidt 2022, p. 168; Carver 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 13–14, 38; Carver 1990, pp. 32–33, 52; Mayer 1969, p. 19; Green 2008, p. 16; Marcus 1974, p. 78; Hunley 1991, p. 2; Carver 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 13; Carver 1990, p. 8; Mayer 1969, p. 16; Henderson 1976, p. 3; Green 2008, p. 17; Hunley 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 19; Green 2008, p. 18; Hunley 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 18; Carver 1990, p. 4; Mayer 1969, p. 16; Green 2008, pp. 16, 18; Marcus 1974, p. 72; Blackledge 2019, p. 21; Hunley 1991, p. 24.

- ^ Carver 2020, p. 23.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 18; Carver 1990, p. 8; Green 2008, p. 19; Schmidt 2022, p. 168.

- ^ Mayer 1969, p. 17; Green 2008, p. 21; Marcus 1974, p. 71; Berger 1977, p. 23; Hunley 1991, p. 6; Carver 2020, p. 24.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 19; Carver 1990, p. 5; Carver 1983, p. 2; Mayer 1969, p. 17; Henderson 1976, p. 6; Green 2008, p. 20; Hunley 1991, p. 5.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 19–20; Carver 1990, pp. 6, 36; Henderson 1976, p. 6; Blackledge 2019, p. 21; Hunley 1991, p. 5; Carver 2020, p. 61.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 25; Carver 1990, p. 8.

- ^ Carver 1990, pp. 8–9; Marcus 1974, p. 72; Berger 1977, p. 23; Carver 2020, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 25; Carver 1990, p. 6; Mayer 1969, p. 20; Henderson 1976, p. 6; Green 2008, p. 22; Marcus 1974, p. 69; Hunley 1991, p. 7; Carver 2020, p. 27; Carver 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Mayer 1969, p. 20; Marcus 1974, p. 70; Hunley 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Carver 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Marcus 1974, p. 72; Hunley 1991, p. 4.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 26; Carver 1990, p. 12; Carver 1983, p. 3; Mayer 1969, p. 21; Henderson 1976, p. 7; Green 2008, p. 25; Marcus 1974, p. 74; Hunley 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. plate 6; Hunley 1991, p. 9.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 26; Henderson 1976, p. 7.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 28; Carver 1990, p. 12; Mayer 1969, p. 21; Green 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Mayer 1969, pp. 21–22; Henderson 1976, p. 9; Green 2008, p. 30; Hunley 1991, p. 8; Carver 2020, p. 33.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 29–30; Carver 1990, p. 15; Green 2008, pp. 30, 34; Carver 2020, p. 40.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 36; Carver 1990, p. 40; Carver 1983, p. 3; Mayer 1969, p. 22; Henderson 1976, p. 9; Green 2008, p. 27; Marcus 1974, p. 77; Schmidt 2022, p. 169; Carver 2020, p. 29; Carver 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Carver 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 38, 40; Carver 1990, pp. 51–55; Carver 1983, pp. 3–5; Mayer 1969, pp. 19, 22; Henderson 1976, pp. 3–4, 10–11; Green 2008, p. 16; Marcus 1974, pp. 77–79; Blackledge 2019, p. 23; Rigby 1992, p. 28; Hunley 1991, p. 2; Kellner 1999, p. 165; Carver 2003, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Schmidt 2022, p. 170; Carver 2020, p. 53.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 41; Carver 1990, p. 44; Mayer 1969, p. 16; Henderson 1976, p. 5; Rigby 1992, p. 31.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 42; Carver 1990, p. 45; Carver 1983, p. 6; Mayer 1969, p. 26; Henderson 1976, p. 5; Marcus 1974, p. 76; Blackledge 2019, p. 22; Rigby 1992, p. 32; Hunley 1991, p. 9; Carver 2020, p. 87.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 42; Carver 1990, p. 48; Rigby 1992, p. 32; Hunley 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 43; Carver 1990, p. 49; Mayer 1969, p. 25; Henderson 1976, p. 5; Marcus 1974, p. 77; Rigby 1992, pp. 12, 21; Hunley 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 44; Carver 1990, p. 49; Carver 1983, p. 9; Rigby 1992, p. 33; Carver 2020, p. 45.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 45; Carver 1990, p. 61; Carver 1983, p. 12; Mayer 1969, p. 35; Henderson 1976, p. 13; Green 2008, p. 35; Marcus 1974, p. 80; Hunley 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 26.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 27.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 47; Carver 1990, p. 80; Henderson 1976, pp. 13–14; Green 2008, p. 36; Hunley 1991, p. 12; Carver 2020, p. 85; Carver 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 47; Carver 1990, p. 65; Carver 1983, p. 12; Mayer 1969, p. 35; Henderson 1976, pp. 15–16; Green 2008, p. 39; Marcus 1974, p. 81; Hunley 1991, p. 12; Carver 2020, p. 87; Carver 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 48; Carver 1990, pp. 68–69; Carver 1983, p. 13; Mayer 1969, p. 36; Henderson 1976, pp. 16, 30–31; Green 2008, p. 42; Marcus 1974, p. 82; Blackledge 2019, p. 22; Rigby 1992, p. 33; Hunley 1991, p. 13.

- ^ Carver 2003, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Carver 2020, pp. 90–94.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 58; Carver 1990, p. 81; Carver 1983, p. 17; Mayer 1969, p. 33; Henderson 1976, p. 14; Green 2008, p. 44; Marcus 1974, p. 81.

- ^ Mayer 1969, p. 34; Henderson 1976, p. 14.

- ^ Blackledge 2019, p. 22.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 73–74; Henderson 1976, p. 16; Green 2008, p. 41; Rigby 1992, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Kurz 2022, p. 26.

- ^ Carver 2003, p. 24.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 75; Carver 1990, p. 72; Carver 1983, p. 15; Mayer 1969, p. 35; Henderson 1976, p. 14; Green 2008, p. 43; Marcus 1974, p. 82; Rigby 1992, p. 33.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 80; Carver 1990, p. 91; Carver 1983, p. 17; Green 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 86; Hunley 1991, p. 14.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 85–86; Carver 1990, p. 96; Carver 1983, pp. 21, 25; Mayer 1969, p. 46; Henderson 1976, p. 19; Green 2008, p. 47; Marcus 1974, p. 89; Blackledge 2019, p. 22; Hunley 1991, p. 14; Carver 2020, p. 65; Carver 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 86; Carver 1990, p. 97; Carver 1983, pp. 23–25; Mayer 1969, p. 46; Henderson 1976, p. 19; Green 2008, p. 47; Blackledge 2019, p. 23; Carver 2020, p. 65; Carver 2003, p. 40.

- ^ a b Carver 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 18; Green 2008, p. 45; Marcus 1974, p. 87; Rigby 1992, p. 38; Hunley 1991, p. 14; Levine 1975, pp. 124–125; Carver 2020, p. 101.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 87, 89; Mayer 1969, p. 46; Henderson 1976, p. 21; Marcus 1974, p. 88.

- ^ Carver 1990, p. 96; Green 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 78–79; Carver 1990, p. 102; Carver 1983, p. 34; Henderson 1976, p. 21; Green 2008, p. 52; Marcus 1974, p. 91.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 26; Blackledge 2019, p. 27.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 98; Carver 1990, p. 149; Mayer 1969, p. 53; Henderson 1976, p. 22; Green 2008, p. 69; Marcus 1974, p. 98; Hunley 1991, p. 15; Carver 2003, p. 34.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 100; Mayer 1969, p. 57; Henderson 1976, p. 22; Green 2008, p. 70; Marcus 1974, p. 98.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 98, 110, 228; Green 2008, pp. 71, 192; Carver 2003, p. 34.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 92, 95–96; Carver 1990, p. 108; Mayer 1969, p. 61; Henderson 1976, p. 22; Green 2008, pp. 61, 64; Marcus 1974, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 23.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 106.

- ^ Carver 2003, pp. 28, 30.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 103; Carver 1990, p. 127; Marcus 1974, p. 91; Hunley 1991, p. 16.

- ^ Nippel 2022, pp. 108, 110; Carver 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Carver 2003, p. 33.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 105, 110; Henderson 1976, pp. 51–53; Green 2008, p. 72; Marcus 1974, pp. 169–172, 204; Carver 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 113; Carver 1990, p. 129; Marcus 1974, p. 138.

- ^ Rigby 1992, pp. 61–63, 71.

- ^ Carver 1983, p. 45.

- ^ Illner, Frambach & Koubek 2023, p. 66.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 101; Carver 1990, pp. 111, 114; Henderson 1976, pp. 24–25; Green 2008, p. 80; Marcus 1974, p. 101; Rigby 1992, pp. 31, 40–41, 45; Kellner 1999, p. 167.

- ^ Kurz 2022, p. 9; Blackledge 2019, p. 24; Hollander 2011, p. 39; Hunley 1991, p. 140; Carver 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Hollander 2011, pp. 8, 31, 40–41; Hunley 1991, p. 15; Kołakowski 1978, p. 161.

- ^ Chaloupek & Frambach 2022, p. 4; Carver 2020, p. 112.

- ^ Kurz 2022, p. 9; Carver 1983, pp. 32, 48, 50; Graßmann 2021, p. 94; Hunley 1991, p. 15; Steger & Carver, p. 21; 1999 & Carver, p. 42; 2003.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 120; Carver 1983, p. 37; Mayer 1969, p. 66; Henderson 1976, pp. 26–27; Green 2008, p. 83; Marcus 1974, p. 113; Blackledge 2019, p. 24.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 123; Carver 1990, p. 175; Carver 1983, p. 49; Mayer 1969, p. 74; Green 2008, p. 85; Marcus 1974, p. 113; Blackledge 2019, p. 35; Hunley 1991, p. 17.

- ^ Carver 2020, p. 113.

- ^ Carver 2020, p. 119; Carver 2003, p. 45.

- ^ Rees 1998, pp. 120, 68–69.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 79; Green 2008, p. 99; Marcus 1974, p. 120.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 85; Green 2008, p. 104; Marcus 1974, p. 129; Hunley 1991, p. 17; Carver 2003, p. 47.

- ^ Rees 1998, p. 117.

- ^ Rees 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 133; Rigby 1992, pp. 77, 81; Perry 2002, p. 149.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 131; Carver 1990, p. 180; Carver 1983, p. 69; Mayer 1969, p. 85; Henderson 1976, p. 85.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 134; Carver 1990, p. 185; Henderson 1976, p. 93; Green 2008, p. 103; Hunley 1991, p. 17.

- ^ Mayer 1969, pp. 103–104; Henderson 1976, p. 100; Green 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 146–147; Carver 1990, p. 181; Carver 1983, p. 85; Henderson 1976, pp. 106, 119; Green 2008, p. 111; Blackledge 2019, p. 24; Carver 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 148; Carver 1990, p. 191; Mayer 1969, p. 107; Henderson 1976, p. 119; Green 2008, p. 114; Blackledge 2019, p. 73; Hunley 1991, p. 66.

- ^ Carver 1983, pp. 85–86; Rigby 1992, pp. 101–102; Hollander 2011, p. 9.

- ^ Perry 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 149.

- ^ Hunley 1991, p. 65.

- ^ Kangal 2022, p. 77; Carver 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 159; Carver 1990, p. 194; Mayer 1969, p. 114; Henderson 1976, pp. 134, 137–138; Green 2008, p. 126; Hunley 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 162; Henderson 1976, pp. 144–145; Kołakowski 1978, p. 250.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 31; Hunley 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 165; Carver 1990, p. 196; Mayer 1969, p. 122; Henderson 1976, p. 149; Green 2008, p. 131.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 166; Carver 1990, p. 196; Mayer 1969, p. 122; Henderson 1976, p. 149; Green 2008, p. 133.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 173; Carver 1990, p. 203; Mayer 1969, p. 131; Henderson 1976, pp. 155–156; Green 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 34.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 174–176; Carver 1990, p. 204; Mayer 1969, p. 132; Henderson 1976, p. 156; Green 2008, p. 145; Berger 1977, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 39; Carver 2003, p. 52.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 178–179; Carver 1990, p. 206; Mayer 1969, p. 137; Henderson 1976, pp. 162–163; Green 2008, pp. 149, 154; Blackledge 2019, p. 103; Berger 1977, p. 41; Hunley 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 178–179; Carver 1990, p. 206.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 42.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. plate 9.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 181; Henderson 1976, p. 165.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 184; Carver 1990, p. 212.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 187; Carver 1990, p. 139; Mayer 1969, p. 157; Henderson 1976, pp. 175, 195; Green 2008, p. 172; Hunley 1991, p. 18; Carver 2003, p. 56.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 89; Carver 1990, p. 135; Green 2008, p. 172; Marcus 1974, p. 117.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 182, 205; Henderson 1976, p. 195; Green 2008, p. 177; Marcus 1974, p. 119.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 191, 215; Carver 1990, p. 141; Mayer 1969, p. 197; Henderson 1976, pp. 197, 215–216; Hunley 1991, p. 24.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 193; Green 2008, p. 178.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 195; Carver 1990, p. 144; Henderson 1976, pp. 205, 224; Green 2008, p. 295; Hunley 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 206; Carver 1990, p. 152; Green 2008, p. 177; Hunley 1991, p. 23.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 210–211; Carver 1990, p. 151; Henderson 1976, pp. 226–229; Green 2008, p. 199; Hunley 1991, p. 23.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 208; Mayer 1969, p. 69; Henderson 1976, p. 210; Green 2008, p. 189; Berger 1977, p. 58.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Carver 1983, p. 95.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 200–201; Carver 1990, p. 213; Mayer 1969, p. 166; Henderson 1976, p. 206; Hunley 1991, p. 18; Carver 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Rigby 1992, pp. 97–99, 106; Liedman 2022, pp. 14, 51.

- ^ Liedman 2022, p. 342.

- ^ Perry 2002, pp. 61–62; Carver 2003, p. 54.

- ^ a b Perry 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Perry 2002, pp. 64–65; Carver 2003, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 220–221; Carver 1990, pp. 222, 227; Mayer 1969, p. 164; Henderson 1976, p. 209; Green 2008, p. 212; Blackledge 2019, p. 19; Hunley 1991, p. 21.

- ^ Illner, Frambach & Koubek 2023, p. 3.

- ^ Berger 1977, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 228; Carver 1990, p. 153; Mayer 1969, p. 207; Henderson 1976, p. 220; Green 2008, p. 192.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 229; Carver 1990, pp. 153–155; Mayer 1969, p. 208; Henderson 1976, p. 221; Green 2008, pp. 192, 307; Marcus 1974, p. 118.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 230; Carver 1990, p. 156; Mayer 1969, p. 210; Green 2008, p. 204; Marcus 1974, p. 118.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 202; Hollander 2011, pp. 285–287, 289–290; Hunley 1991, p. 134.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 202; Hunley 1991, p. 134.

- ^ Graßmann 2021, pp. 99–103.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 239; Carver 1990, p. 248; Henderson 1976, pp. 404–405; Hunley 1991, p. 142; Carver 2003, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 241; Carver 1990, p. 141; Henderson 1976, p. 218; Green 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 241; Carver 1990, p. 142; Mayer 1969, p. 227; Henderson 1976, p. 218; Green 2008, p. 187.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. i, 241; Hunley 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 245, plate 24.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 242; Carver 1990, p. 157; Mayer 1969, p. 235; Green 2008, p. 231; Hunley 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 243; Henderson 1976, p. 520; Hunley 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 257; Mayer 1969, p. 243; Henderson 1976, p. 529; Green 2008, p. 242.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 259, 260; Carver 1990, p. 242; Mayer 1969, p. 253; Henderson 1976, pp. 541–544; Kołakowski 1978, p. 246.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 250.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 249; Green 2008, p. 262.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 249–250; Mayer 1969, p. 293; Green 2008, p. 266.

- ^ Kangal 2022, p. 81; Liedman 2022, p. 345; Carver 2003, p. 70.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 296; Carver 1990, p. 244; Carver 1983, p. 119; Mayer 1969, p. 266; Henderson 1976, pp. 586–590; Green 2008, p. 240; Blackledge 2019, p. 180.

- ^ Carver 1983, p. 121.

- ^ Liedman 2022, pp. 115, 322.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 298; Carver 1990, p. 250; Mayer 1969, p. 271; Henderson 1976, p. 591.

- ^ Thomas 2008, p. 50; Carver 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Liedman 2022, pp. 13, 318–319; Kangal 2021, p. 69; Hunley 1991, p. 30; Carver 2003, p. 77.

- ^ Kangal 2022, p. 81.

- ^ Frambach 2022, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Illner 2022, pp. 160, 164.

- ^ Carver 1983, pp. 127–128; Liedman 2022, p. 344; Thomas 2008, p. 78; Carver 2003.

- ^ Liedman 2022, pp. 17, 319.

- ^ Thomas 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 299; Carver 1990, p. 158; Mayer 1969, p. 273; Green 2008, pp. 248, 260; Hunley 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 278; Carver 1983, p. 118; Henderson 1976, p. 568.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 280; Carver 1990, p. 246; Mayer 1969, p. 280; Henderson 1976, p. 569; Thomas 2008, p. 10; Perry 2002.

- ^ Carver 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 658; Green 2008, p. 250; Blackledge 2019, p. 10.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 322.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 658.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 303; Mayer 1969, p. 281; Henderson 1976, p. 658; Green 2008, p. 268; Blackledge 2019, p. 165.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 304, 341; Carver 1990, p. 249; Green 2008, p. 268; Hunley 1991, p. 33.

- ^ van Holthoon 2022, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Illner, Frambach & Koubek 2023, p. 224.

- ^ Graßmann 2021, pp. 103–104, 112.

- ^ Kurz 2022, p. 31.

- ^ Chaloupek 2022, pp. 50–51; Blackledge 2019, p. 173; Hollander 2011, pp. 111–119, 307.

- ^ Blackledge 2019, pp. 166–167; Hollander 2011, pp. 305, 308–309.

- ^ Henderson 1976, p. 605; Carver 1983, p. 144; Green 2008, p. 265; Hunley 1991, p. 31; Carver 2003, p. 85.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 197.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 310; Carver 1990, p. 245; Green 2008, p. 266; Rigby 1992, pp. 199–200; Gould 1999, p. 272; Carver 2003, p. 86.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 309; Blackledge 2019, pp. 207, 220.

- ^ Rigby 1992, p. 200; Sayers, Evans & Redclift, p. 56; Gould 1999, p. 273; 1987.

- ^ Perry 2002, p. 15.

- ^ a b Perry 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Perry 2002, pp. 62–63; Carver 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Perry 2002, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 339; Mayer 1969, p. 322; Henderson 1976, p. 716; Green 2008, p. 275.

- ^ Dalvit 2022, pp. 141–142, 148–150.

- ^ Rogers 1992, p. 117.

- ^ Wilde 1999, p. 215; Berger 1977, p. 159.

- ^ Berger 1977, pp. 161–162, 166.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 342; Mayer 1969, p. 335; Green 2008, p. 333; Blackledge 2019, p. 225; Rigby 1992, p. 231; Steger 1999, p. 210.

- ^ Rogers 1992, pp. 56, 73–74.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 351; Mayer 1969, p. 357; Green 2008, p. 284; Rogers 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 353; Carver 1990, p. 253; Mayer 1969, p. 358; Henderson 1976, p. 727; Hunley 1991, p. 45; Rogers 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Rogers 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 353–354; Mayer 1969, p. 359; Green 2008, p. 299; Hunley 1991, p. 45.

- ^ a b Hunt 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 249, 250.

- ^ Schmidt 2022, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 244; Carver 1990, p. 15; Mayer 1969, p. 22; Henderson 1976, p. 9; Green 2008, p. 30; Hunley 1991, p. 34.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 230, plate 19.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 278; Marcus 1974, p. 128.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 121, 230; Henderson 1976, p. 13.

- ^ Blackledge 2019, p. 8; Hunley 1991, p. 144.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 98, 228; Carver 1990, pp. 149, 153; Mayer 1969, p. 207; Henderson 1976, p. 220; Green 2008, p. 192.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 230; Mayer 1969, p. 273; Green 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 299; Carver 1990, p. 158; Mayer 1969, p. 273; Hunley 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 311; Blackledge 2019, p. 213.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 204, 353; Henderson 1976, pp. 203, 727; Green 2008, p. 297; Hunley 1991, p. 42.

- ^ Carver 1990, pp. 165–171; Carver 2003, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 300; Mayer 1969, p. 271; Henderson 1976, pp. 591, 730.

- ^ Rogers 1992, p. 74.

- ^ Berger 1977, p. 174.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 5–6, 301; Green 2008, pp. 325–326; Blackledge 2019, p. 1; Rigby 1992, pp. 4–5; Thomas 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 5–6, 301; Green 2008, p. 326; Blackledge 2019, pp. 1–2; Rigby 1992, pp. 6, 96; Hunley 1991, p. 50; Levine 1975, pp. xv, 137; Rockmore 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Levine 1975, pp. xv, 215, 235.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, pp. 402, 405; Thomas 2008, p. 57.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, pp. 402, 405.

- ^ Thomas 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Hunt 2009, pp. 301, 361; Blackledge 2019, pp. 12–13; Hunley 1991, p. 49; Levine 1975, pp. xvi–xvii; Thomas 2008, pp. 55, 112–113.

- ^ Kangal 2022, p. 84.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 408; Kangal 2022, p. 84.

- ^ Thomas 2008, p. 52.

- ^ Blackledge 2019, p. 181.

- ^ Rees 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Rees 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Rees 1998, p. 252.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 301; Rigby 1992, pp. 154, 162–163.

- ^ Blackledge 2019, pp. 6, 8.

- ^ Kangal 2022, pp. 80, 85.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 365; Blackledge 2019, p. 13.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 366.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 367.

- ^ Carver 1990, pp. 259, 286; Carver 1983, p. 154.

- ^ Liedman 2022, pp. 487–488, 535.

- ^ Sayers, Evans & Redclift 1987, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Sayers, Evans & Redclift 1987, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Brown 2021, pp. 204, 207–208.

- ^ Sayers, Evans & Redclift, p. 18; 1987 & Gould, p. 276; 1999.

- ^ Sayers, Evans & Redclift 1987, pp. 15, 17.

- ^ a b Hunt 2009, p. 368.

- ^ Brophy 2022, pp. 121, 134.

- ^ Blackledge 2019, p. 197.

- ^ Royle 2021, pp. 171, 181, 187.

- ^ Hunt 2009, p. 369.

Works cited

[edit]- Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A., eds. (2022). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Brophy, James M. (2022). ""Economic Facts Are Stronger Than Politics": Friedrich Engels, American Industrialization, and Class Consciousness". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 121–140. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Chaloupek, Günther (2022). "Engels, Werner Sombart, and the Significance of Marx's Economics". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 47–67. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (2022). "Introduction". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Dalvit, Paolo (2022). "Engels' Strategic Advice to the Representatives of the Italian Labour Movement". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 137–155. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Frambach, Hans A. (2022). "Friedrich Engels and Positivism: An Attempt at Classification". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 63–81. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Illner, Eberhard (2022). "Friedrich Engels and Electricity". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 153–169. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Kangal, Kaan (2022). "Engels' Conceptions of Dialectics, Nature, and Dialectics of Nature". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 77–95. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Kurz, Heinz D. (2022). "Friedrich Engels at 200 Revisiting His Maiden Paper "Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy" (1844)". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 9–42. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Nippel, Wilfried (2022). "Remarks on the Embarrassed Publishing History of Engels, Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 107–124. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Schmidt, Karl-Heinz (2022). "Two Sides of Young Friedrich Engels: Private Letters and Professional Studies". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 167–178. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- van Holthoon, Frits (2022). "Friedrich Engels and the Revolution". In Backhaus, Jürgen G.; Chaloupek, Günther; Frambach, Hans A. (eds.). 200 Years of Friedrich Engels: A Critical Assessment of His Life and Scholarship. Cham: Springer. pp. 91–110. ISBN 978-3-031-10115-1.

- Berger, Martin (1977). Engels, Armies and Revolution: The Revolutionary Tactics of Classical Marxism. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books. ISBN 0-208-01650-3.

- Blackledge, Paul (2019). Friedrich Engels and Modern Social and Political Theory. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-7687-2.

- Carver, Terrell (1983). Marx & Engels: The Intellectual Relationship. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33681-3.